We met Néstor building his father’s tomb. So high up in the valley that the wind whipped around the cemetery’s tombstones and crept under our collars. A chill emanated from the mountainside and the dilapidated headstones covered in silk and paper flowers and rudimentary crosses. Néstor’s father had been dead six months, but was buried in Escoipe, the nearest city.

We met Néstor building his father’s tomb. So high up in the valley that the wind whipped around the cemetery’s tombstones and crept under our collars. A chill emanated from the mountainside and the dilapidated headstones covered in silk and paper flowers and rudimentary crosses. Néstor’s father had been dead six months, but was buried in Escoipe, the nearest city.

Néstor’s mother, still living insisted that they fulfill his father’s wish to be buried in the community cemetery, overlooking the thin sliver of green that snaked along the bottom of the Valle Encantado. “The cemetery has been here since the 70s or 80s,” said Néstor, “It’s for all the families that live in the surrounding hills.” “Not me,” he adds defensively “I live in the city.” And in a vision I see them, stooped women with heads covered in black lace, a mother gathering her children under a black umbrella for warmth against the wind and against death. The gravediggers with coca leaves packed into their cheeks patiently waiting … it’s a long walk home.

A few miles down the road is the señora who sells the coca leaves … and zinc and cinnamon fig preserves and miniature cacti. This is nothing, she tells us, where I grew up as a child was over 3,000 meters, I don’t even notice the altitude, her arms crossed in front of her solid, square, indigenous body. She has three lazy dogs, two kittens and the greatest view from an outhouse I have ever seen.

Outside of Cachi, at the Miraluna ranch, 8-year-old Cristian is waiting to tell us  about Zombies vs. Plants, his favorite video game. He is especially fond of the zombie parrot (who sits on the shoulder of none other than the zombie pirate) because he doesn’t eat brains, only plants. As if he were his mother’s ventriloquist doll he tells me that the public school he attends is just no good at all, too many of the children use bad words and the books are outrageously expensive.

about Zombies vs. Plants, his favorite video game. He is especially fond of the zombie parrot (who sits on the shoulder of none other than the zombie pirate) because he doesn’t eat brains, only plants. As if he were his mother’s ventriloquist doll he tells me that the public school he attends is just no good at all, too many of the children use bad words and the books are outrageously expensive.

Between them, his parents have over 10 siblings. Some live in Cachi, some in Salta and some moved to Buenos Aires because of a family “misunderstanding” Christian tells me. He’s painting a rather disorganized picture of his father Elvio, the manager, saying that he not only losses his cellphone all the time, but that he somehow managed to start a fire playing Jenga. Huh?

I’m convinced that Elvio is probably a pretty responsible guy, especially when he takes us on a tour and expounds upon his newfound passion for wine-making. “I always thought that drinking meant changing your personality,” he tells us, explaining that his father’s alcoholism kept him from drinking until a few years ago. He pours us a glass of this year’s Malbec, still fermenting in the bodega’s steel tanks. It’s still acidic and strong, not easy on the palate at 11am.

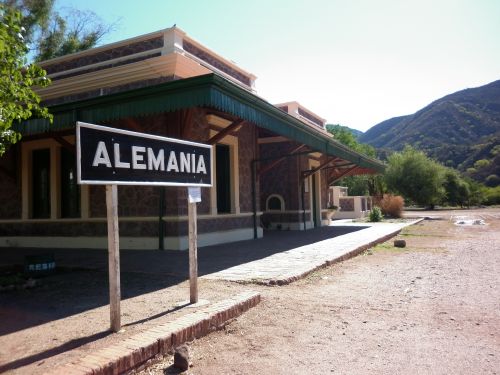

Elsa lives in Alemania (Germany) with 49 other people. She is standing in front of the town’s now abandoned train station. The desert sun has baked Alemania’s streets and a mangy dog is our only welcome committee. Elsa believes that her upcoming restaurant, where she plans to serve empanadas, might be the draw  that tourists need to spend more than 5 minutes in Alemania looking at the old station.

that tourists need to spend more than 5 minutes in Alemania looking at the old station.

Up until 1972, trains from Salta (107 kilometers away) would take passengers all the way Alemania — the end of the line. The rail line was supposed to continue to Cafayate in the southern part of Salta province, but that section was never built, new modes of transportation took its place. Now the place is a ghost town with one lonely woman looking to make it lively once again.

We picked up Norma in Payogastilla, on our way to San Carlos to check out a craft brewery there. A big, smiling woman she reminded me of Mercedes Sosa, with a voice to match. She has worked for over 30 years as a nurse in her tiny town of 75 people. She helps run the only Centro de Salud within miles, where they see high levels of patients with respiratory diseases in the winter and diarrhea in the summer. Since there’s no phone and no ambulance, major emergencies require Norma keeping patients stable and alive while she sends someone to La Merced, the town 5 kilometers down the road to call for an ambulance. That’s what happened when a truck overturned with 11 young workers in it. They saved all but two.

Ricardo is the Pigüé cathedral’s regular gardener but not the day we met him. At over 90 degrees in mid-afternoon he had decided to take a break and come back tomorrow. He’s originally from Puán, five miles away but likes Pigüé well enough. “Except for the drugs,” he says with a frown. “There are a lot of drugs coming through. Mexico too, no?” I nod my head yes and wonder how much drug trafficking this town of 13,800 in the middle of the Argentine Pampas can really be experiencing. He tells me he’s been interviewed before, by the regional newspaper, a story about the history of Pigüé and we talk about the annual world’s biggest omelet festival. This year, he tells me, they used over 20,000 eggs.

Outside of Pigüé, in search of the “demonstration garden” advertised in the  tourist office we instead found a kind of Argentine petting zoo in Cacho Zavala’s backyard. It starts with his llama, Pepe, who I got out of the car to take a picture of. From there he introduced us to Lola and Manuel, two dogs with a new litter of pups, his skinny little piglets, the geese, Chita the motherless lamb that followed him around like a dog and all the tiny chicks in the backyard shack. After our tour he tells us to come back any time — and that next time we’ll all drink a mate.

tourist office we instead found a kind of Argentine petting zoo in Cacho Zavala’s backyard. It starts with his llama, Pepe, who I got out of the car to take a picture of. From there he introduced us to Lola and Manuel, two dogs with a new litter of pups, his skinny little piglets, the geese, Chita the motherless lamb that followed him around like a dog and all the tiny chicks in the backyard shack. After our tour he tells us to come back any time — and that next time we’ll all drink a mate.

Click here to subscribe via RSS