Update: This article has been modified from its original version to more fully explain the situation that occurred at Merida #90 in the Roma Norte.

Every neighborhood changes. People move in and out and back again with shifts in politics, prices and prejudice. It’s often hard as a newcomer to truly appreciate the evolution of the past two years, ten years, or half century of streets where you live, but it’s important history for understanding the social fabric and politics of a location.

I have a particular obsession with the elements that make cities livable, a passion ignited by my first reading of “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” by Jane Jacobs.

I have a particular obsession with the elements that make cities livable, a passion ignited by my first reading of “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” by Jane Jacobs.

In this urban planning bible, Jacobs evaluates why certain cities (and individual neighborhoods within them) either flourish or fail, why some parks are abandoned and others maintained, why areas with a certain mix of buildings have a more vibrant street life.

In Jacob’s view, the best neighborhoods develop gradually and mingle buildings that vary in age and condition, including a good proportion of old ones. This kind of development allows for mom and pop shops and supermarket chains, for low-wage workers and high-class executives to all take part in the social cohesion that makes neighborhoods safe, diverse and economically viable.

Mexico City’s La Roma is an example of one of those mixed neighborhoods. It’s had a long history of poets, artists and vagabonds (including such characters as William S. Borroughs, Jack Kerouac, Remedios Varo and María Izquierdo) and has also been home to Mexico City’s high society.

Where the colonia now sits was once acres of abandoned fields just outside of Mexico City surrounding a small rural town called La Romita. In 1903, developer Edward Walter Orrin presented plans to the local city hall for the building of a suburb with wide, tree-lined boulevards and European-inspired architecture – La Roma. It was to become the home of Mexico City’s second-tier rich moving out from the historical center, who fifty years later would abandon it for neighborhoods like Polanco, Anzures and Las Lomas.

In the past few decades the neighborhood’s location, architecture, and social scene has made it once again the place to live.

According to Ricardo Nurko, an architect who lives and works in La Roma,”Six or seven years ago this place was abandoned at night, no one was in the street past eight o’clock and to be honest, it wasn’t that safe to walk around after dark. Now look at it!”

That said older residents and some new ones are concerned that while gourmet restaurants, hipster bars and delightful outdoor cafes have provided La Roma residents with plenty of nightlife, they have also brought higher rents and a new population of residents with no long-term memory of the neighborhood.

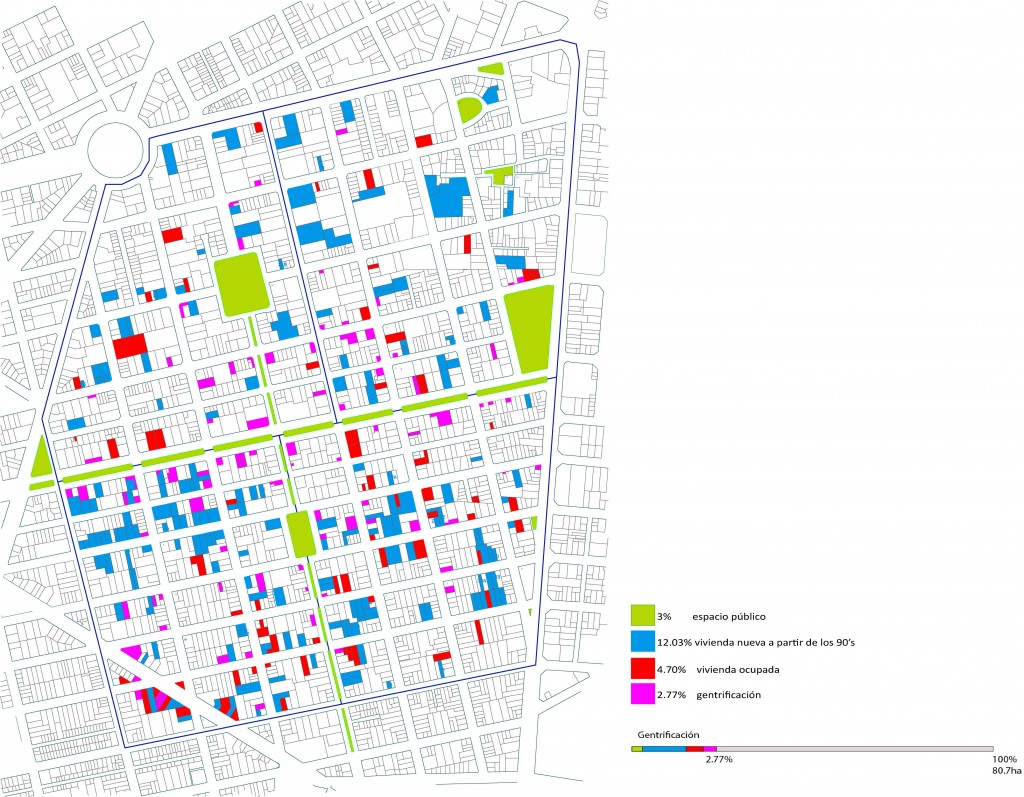

Talking to some of those neighbors is what pushed me to investigate the housing and history of my new home and part of what prompted Nurko and photographer Livia Radwanski to study the neighborhood’s process of gentrification. Nurko and Radwanski set out in 2012 to map out what percentage of Roma’s buildings were new, how many had been taken over, or “occupied” by residents and how many could be considered gentrified. What they found were some interesting statistics, a complicated web of neighborhood politics and a tenuous sense of ownership for some of the neighborhood residents.

Gentrification is generally thought to be an increase in rents or home prices due to higher-income earners moving into an area that was previously working class. These new residents (and the businesses that either follow or attract them) can slowly drive out long-term residents. It’s a common pattern in big cities across the globe; most neighborhoods go from lower to higher income and back again at least once during their lifetimes.

Gentrification is generally thought to be an increase in rents or home prices due to higher-income earners moving into an area that was previously working class. These new residents (and the businesses that either follow or attract them) can slowly drive out long-term residents. It’s a common pattern in big cities across the globe; most neighborhoods go from lower to higher income and back again at least once during their lifetimes.

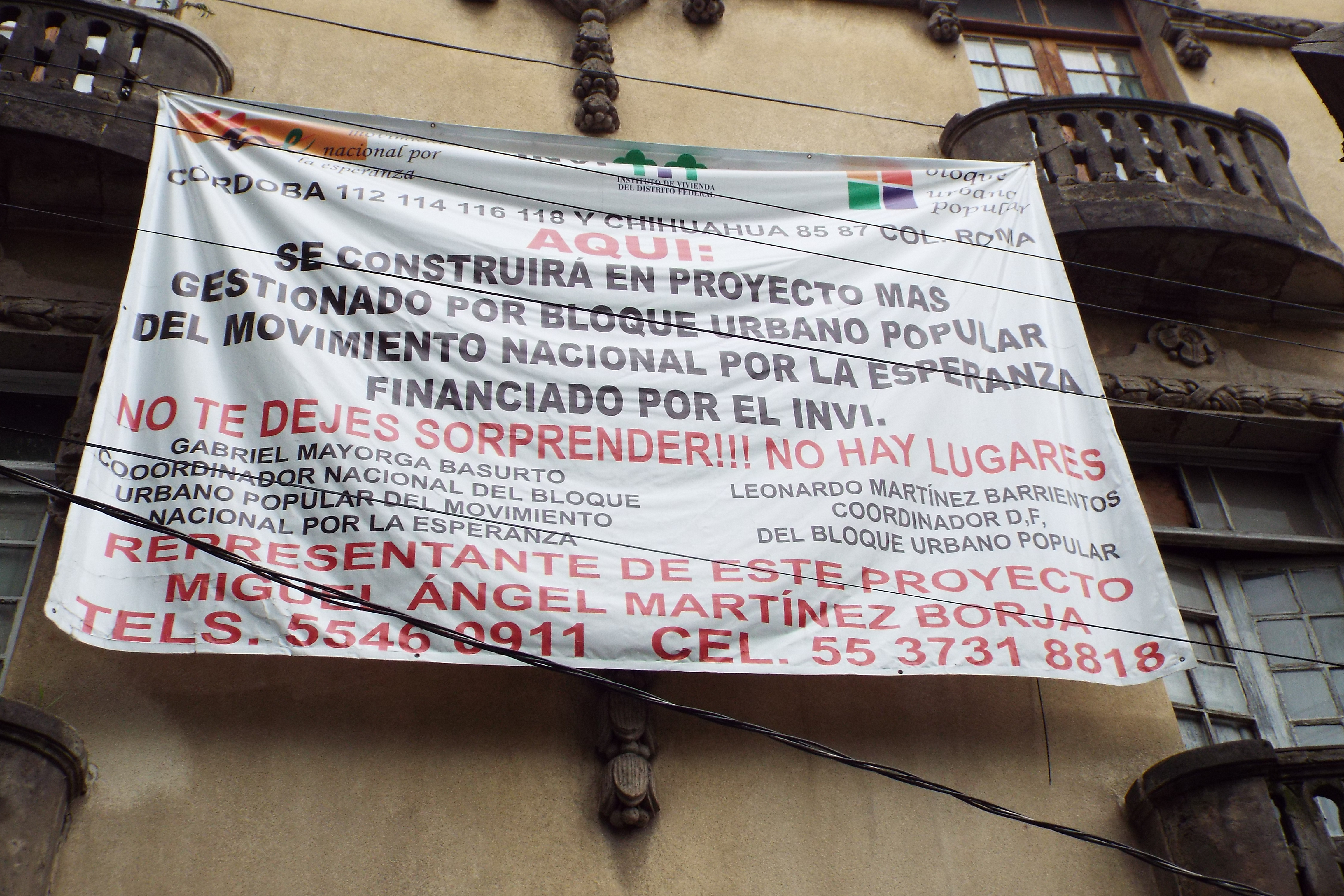

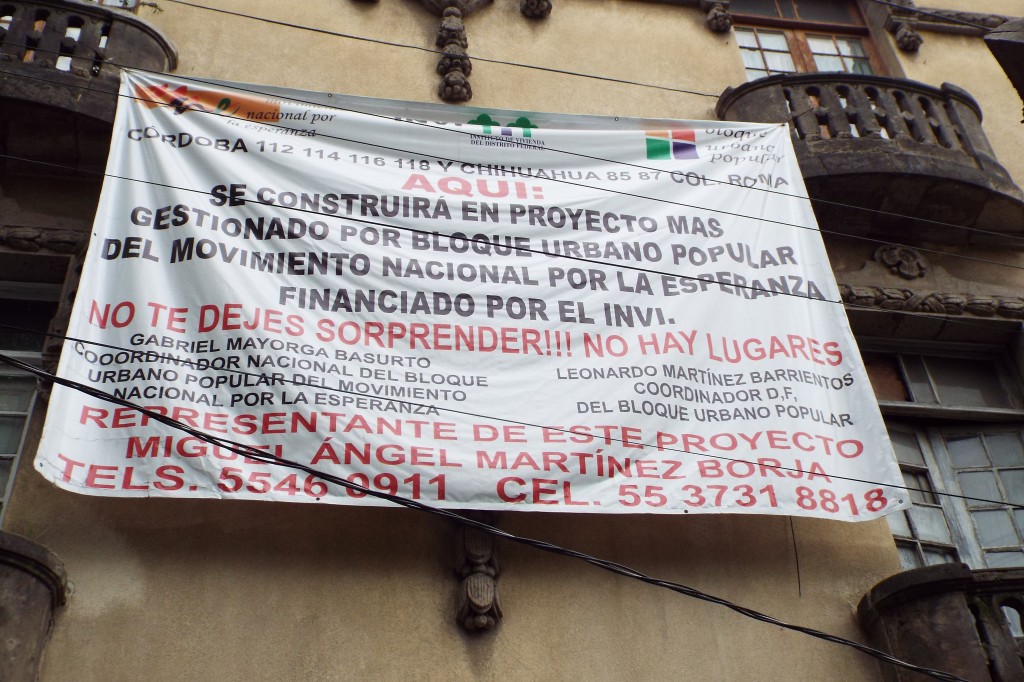

Nurko and Radwanski’s interest in the changing housing landscape of the neighborhood was piqued by a particular situation happening at Mérida #90. Some apartments in this building (that were damaged by the 1985 earthquake) were being occupied by a group of tenants. They were in the middle of a legal battle with the owner when Radwanski moved into a building across the street. Radwanski wrote a book about what was happening there called Merida90 and it became the catalyst for she and Nurko’s broader, joint project later on.

Before you read the term occupied and immediately envision militant squatters huddling around trashcan fires, you must understand that in most cases buildings were occupied by residents already living in them.

This is how they came to occupy them as explained by Nurko: The process was directly related to two major moments in the neighborhood’s history. The first was the rent freeze law put in place after World War II by president Manuel Ávila Camacho in order to control inflation. This law made the neighborhood virtually rent controlled until the 1990s. Property owners claimed that the rising cost of maintenance and taxes were no longer covered by what they could charge in rent. In many cases owners simply abandoned their buildings, leaving them to either be taken over by the residents already living there or occupied by outside groups.

The second major factor was the 1985 earthquake that rocked Roma and left a wake of destruction in the form of dilapidated and unstable buildings. Many of these buildings were also abandoned by owners with no money to repair them.

Some occupations of abandoned or damaged properties were led by political groups. They organized residents to take over the buildings, providing them with housing in exchange for political loyalty. Much of the money flowing into the buildings’ renovation and the renovations themselves depend on political sway and control.

According to Nurko, as the real estate boom has hit the Roma in the last five years or so, many children and grandchildren of the original owners of these buildings have come back to claim their property. In certain cases the government has interceded to purchase the properties and offer residents avenues to secure right of ownership.

It doesn’t always turn out the way tenants expect.

In the case of Mérida #90, residents petitioned the government to expropriate the building because the original owner was no longer around or keeping up the building. The government won expropriation and had five years to remodel the building before the original owner technically had the right to reclaim it. The government drug its feet, waiting until almost the entire five years where up and the residents, right before the deadline was about to expire, hired a lawyer to fight for their right of ownership, using the dignified housing defense which is part of Mexican law. They won their case, but were forced to move anyways as the government began the remolding process. It’s now been four years since the renovation began and families are still waiting to return to their homes. Most living in the periphery of the city, unsure when they will be able to return.

Complaints fly from both sides about occupied buildings, from families who depend on these buildings for affordable housing and others who see the buildings as eyesores and wasted potential. What is not often discussed is that these buildings are an integral part of La Roma’s social cohesion. They not only serve as a barrier to further physical gentrification of the neighborhood, but also provide space for lower income, long-term residents who play an important part in conserving Roma’s economic, political and social diversity.

Through their research, Nurko and Radwanski found that of the neighborhood’s entire area, public parks and green space constitute 3%, new residential buildings (built after 1990), 12.3%, occupied buildings 4.7%, and properties converted into shops or restaurants (their definition of “gentrified”), 2.77%. A stroll around the neighborhood will show you that the percentage of gentrified and new residential properties is only going to continue to rise as long as La Roma continues to draw investors with its growing economy and attractive cultural atmosphere. According to this business insider piece, La Roma as a neighborhood compares with some of the most gentrified U.S. cities, like San Francisco with 13% gentrified land and New York with 18%.

According to Nurko, he and Radwanski’s project was conceptualized as a way to bring awareness to the issue of gentrification in this neighborhood, not an explicit political statement about what the solution should be. They believe that the statistics they discovered are important to look at as La Roma decides what kind of a neighborhood it will be and how it will develop in the future.

“I know that as a resident of the Roma, whether new or old, it’s easy to just go to your favorite coffee shop or restaurant and simply not be aware of what’s happening here. We just wanted to force people to see it,” Ricardo explains.

Healthy cities are organic, spontaneous, messy, complex systems, says Jacobs in her book, but they are also cities where city planners, politicians, and neighbors all have a say in the future of their space. Neighborhood evolution is inevitable, but it may be worth thinking about how we want it to happen.