Every single day of 13 years I have been living in Mexico City has seen me aching to photograph something. Maybe it’s a family dress identically on the metro going to the game or maybe a beggar with an incredibly etched face that I can’t tear my eyes away from, maybe it’s the hodgepodge skyline that extends out in front of me from my rooftop. I usually chicken out when it comes to shooting people and stand in awe of the photographers who are bold enough to ask that simple question: “Can I take your picture?”

Over coffee recently I found myself listening to some great stories from Keith Dannemiller, a documentary photographer who shoots in Mexico City’s Centro Histórico. He‘s recently started to take tourists down to the Centro on photography tours. I asked him how exactly he came to take photos in one of Latin America’s biggest metropolises and how he gets up the nerve to ask that one terrifying question. Here’s some of what he told me:

I arrived in Mexico City on May 5, 1987 because something was missing in my life, professionally and personally. I had been working sporadically for the previous 5 years in Central America and Mexico from my home in Austin, Texas. My work had provided me with contact at the Mexican photo agency Imagenlatina, and I immediately went there to renew the old connection. Turned out that my contact had split from the agency and gone on to form his own. With my comic book Spanish, I conveyed my desire to stay and work with Imagenlatina to cover political and social events alongside them.

I arrived in Mexico City on May 5, 1987 because something was missing in my life, professionally and personally. I had been working sporadically for the previous 5 years in Central America and Mexico from my home in Austin, Texas. My work had provided me with contact at the Mexican photo agency Imagenlatina, and I immediately went there to renew the old connection. Turned out that my contact had split from the agency and gone on to form his own. With my comic book Spanish, I conveyed my desire to stay and work with Imagenlatina to cover political and social events alongside them.

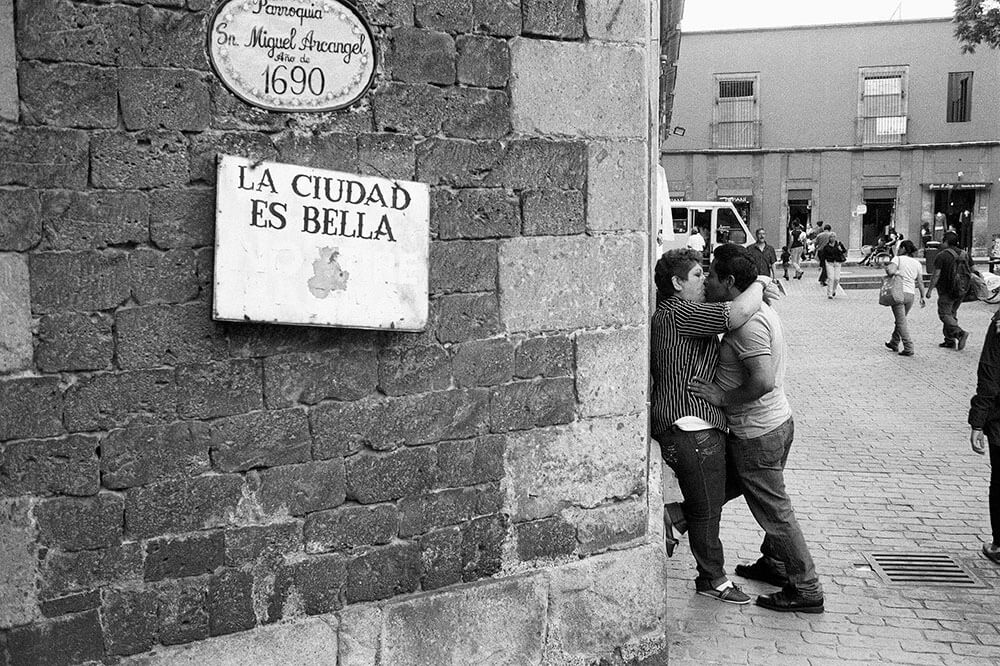

It was a baptism under fire, a total immersion in photojournalism Mexican-style. Beside the halls of political power, they showed me the people and the streets of the city, especially the Centro Histórico, where marches and protests almost always seemed to end. This was my introduction to the area of the city that has served as my muse, my refuge, and my sanctuary.

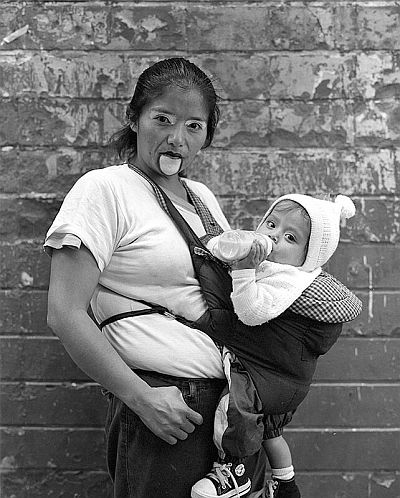

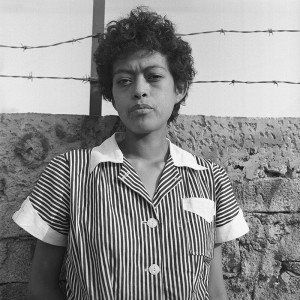

I am a documentary photographer, which means reality is the raw material of my images in both my editorial work and what I shoot on the streets of the Centro. My personal work on those streets though is a bit more loose, spontaneous and open-ended. I shoot on black and white film with a Leica camera that lets me move about a bit more easily. It is not a large DSLR photojournalist-type camera, but small and almost silent when the shutter goes off. It lets me get closer to things happening on the street without being totally perceived as making photos.

Although a 6’1” gringo does not go unrecognized on any street in Mexico City. In a sense, those characteristics may  actually help me. I think many people look at me as a strange tourist and leave me be, to do my thing. I don’t intentionally try to hide what I do when shooting, so a certain quickness coupled with a gut feeling of what I want to photograph usually works pretty well. I work like this on the photo tours I give, but also realize not everyone is with me to take the same kind of images that I do. So we usually expand the visual possibilities while we walk. I try to point out architecture, details, abstract constructs of light and shadow, etc. While it is didactic, with a good bit of photo instruction, including technical aspects, the idea of the walks is to have fun, go down the less traveled streets and not be afraid of making the photograph that you envision. Mexico City, and especially the Centro can be intimidating. We don’t walk in areas that are dangerous, but we aren’t just taking photos of the front of Bellas Artes either. If someone wants to venture into an area that might be a bit more dicey, I have a friend who knows the Centro and can act as an ‘assistant’, if need be.

actually help me. I think many people look at me as a strange tourist and leave me be, to do my thing. I don’t intentionally try to hide what I do when shooting, so a certain quickness coupled with a gut feeling of what I want to photograph usually works pretty well. I work like this on the photo tours I give, but also realize not everyone is with me to take the same kind of images that I do. So we usually expand the visual possibilities while we walk. I try to point out architecture, details, abstract constructs of light and shadow, etc. While it is didactic, with a good bit of photo instruction, including technical aspects, the idea of the walks is to have fun, go down the less traveled streets and not be afraid of making the photograph that you envision. Mexico City, and especially the Centro can be intimidating. We don’t walk in areas that are dangerous, but we aren’t just taking photos of the front of Bellas Artes either. If someone wants to venture into an area that might be a bit more dicey, I have a friend who knows the Centro and can act as an ‘assistant’, if need be.

What are the particular peculiarities of shooting here?

As you have probably gathered, people are the focus of much of my work as a photojournalist and a documentary toronto headshot photographer. I think both of those disciplines influence one another in my work. I try to shoot a bit more spontaneously when doing stories for magazines or portals. And when I’m on the street in the Centro, I know the photojournalist in me is concerned with showing the reality of people who don’t have a voice, who the system has forgotten, and that consideration comes through in my documentary work on the streets. But people are people, anywhere you go. So for me, my approach to working in Mexico is exactly the same as working anywhere else the first operative principle is respect. I relate to subjects and treat them as I would like to be treated. Seems like a simple premise, but you would be surprised how many photographers don’t abide by it.

There are obviously moments, especially in Mexico City and the Centro, so full of photographic possibility that they push the boundaries of a potential subject’s public space and can make the photographer question his own limits of civility. It is a balancing act between the notions of public and private that sometimes has a bit of a dare, a tad of danger involved. But it is also something that, with time, walking and photographing strangers, one develops a type of visceral warning system that let’s you know how far to go, how close to get.

How do you approach people when you want to take their photo?

I do a lot of portraits wherever I shoot. But photographing strangers on the street, in a foreign country, even assuming you speak the language, is never easy. There are cultural norms that the photographer should be aware of before even attempting to approach someone for a direct photographic portrait. I mean this is a city where people still greet total strangers when they take a seat on crowded public transport vehicles.

As I mentioned above, respect for the person you want to photograph is a good starting point. Then after that, honesty. Why do you want to make a portrait of someone you have never met before? Whatever the reason, approach them, say hello and make sure the camera you are using is very visible. It gives a nonverbal signal as to why you might be greeting them out of the blue and is sort of a soft entrance mechanism. Usually, I immediately let them know what I am doing ( “I am photographing in the Centro and working on a book about the area.” “I am here with a small photography class and I am showing people various photographic techniques.”) Then you should let them know very directly that you would like to photograph them and why. ( “I like your look and how you are dressed. Could I make a portrait of you?” “There are not a lot of people anymore who do what you are doing. Would you mind if we photographed you working? You don’t have to do anything out-of-the-ordinary, just continue with what you were doing, please.) It doesn’t even have to be that formal a lot of the time. A gesture with the camera and a few words can help to retain the original scene that attracted you in the first place.

What have some reactions from subjects been?

As nice as you might be in approaching someone for a photo on the street, you have to remember that you are a stranger asking them to pose for a photo. That in and of itself can be frightening to some people, especially when you think about the use of photos on the internet and social media today.

As nice as you might be in approaching someone for a photo on the street, you have to remember that you are a stranger asking them to pose for a photo. That in and of itself can be frightening to some people, especially when you think about the use of photos on the internet and social media today.

When I stop and think about it, I sometimes ask myself, ‘Why would anybody agree to be photographed by some strange man, obviously a foreigner, out here in the middle of a big city?’ So, many times, the question you have to be prepared for is, ‘Why?’. That usually requires more conversation to convince someone that you are not operating with bad intentions and truly are interested in making a portrait of them. This may be a skill I have developed over the years by photographing on the street. I don’t know. And obviously, there are those interesting faces who will say ‘No’, ‘No pictures.’

There is also a notable phenomenon in the Centro that contributes to this rejection that of wanting to take a photo of someone who is engaged in an illegal, or sketchy activity. Obviously, street vendors, selling behind the Palacio Nacional or in Tepito, when they see a camera will be in your face telling you to put it up and don’t shoot. There are streets that I like to walk where I won’t even take the camera out because I know there is no possibility of photographing. To balance it all out are the serendipitous encounters with someone who literally opens their arms to receive you and bares their soul to your camera. Those moments are rare, but so gratifying.

What are some of the best experiences you’ve had on the street here taking photos?

I can say without a doubt that the best experiences I have had photographing on the street have to do with the people who I have been fortunate enough to meet, who have given me the opportunity to take their portraits, and with whom I have continued to be friends. If I photograph someone and carry on a conversation afterward, I will make an effort to return to where they work or hang out with a print or two for them. I feel this is the least a photographer can do for the person who has opened

themselves up to you. There’s Roque, the shoeshine guy who speaks good English that he learned in the Reclusorio Oriente ( a Mexico City penitentiary); Mariana, who collects cardboard refuse and sleeps in a doorway on Junipero Serra St.; Hilario, who sings classic Mexican songs with a megaphone for tips from café patrons in the Condesa and Polanco; Sr. ‘Pipo’, the ex-flyweight boxer who now works in the family shoe repair shop as a cobbler; many of the boxers, male and female at the Nuevo Jordan gym. I love being able to walk around, stop and chat or go for a coffee with them when I’m in the Centro.

What about some of the worst?

I was working on a project of street portraits with a medium format camera. It is a bit cumbersome because it produces a larger negative with an incredible quality. This was with black and white film also. I was obviously much more visible as a ‘serious photographer’ when I went around with that camera. One day I was attracted by some guys welding at the far end of an empty parking garage. Sparks flying are a magnet for photographers. I started walking towards the back of the place and after about ten steps in, was assaulted, robbed and left bleeding from a gun butt to the forehead.

I spent some time in the hospital and fortunately, there were no major repercussions. Needless to say, that project came to a stunning end. That which up until that point had always felt so welcoming, the Centro Histórico, suddenly took on a heavier ambiance for me. I knew why it had happened and that I had crossed some imaginary line of security, but I didn’t know exactly what to do after recovering. It took some time and some confrontations with my own fears about being on the streets of downtown, but I had no choice but to return with a new way of walking. I only bring this event up to illustrate to people that risks are involved when you are on the streets of the Centro with a camera by yourself. A lot of times the most interesting places and people carry a bit of unpredictability no question about it. The trick is obviously how to gauge that and be able to enjoy photographing.

What is the most surprising thing you think people learn on your tours?

It’s not something photographic. I think many people come with some negative ideas about the Centro as a dangerous place where you don’t want to be walking around with a camera. I try to project just the opposite vibe. It is a wonderfully vibrant, visually interesting area to be with a camera. You have to be prepared and take some precautions ones that anyone would take in most any big city. But once you do that and can move with assurance, you are ready for a unique experience in an uncommonly accessible city.

If you want to experience it for yourself, sign up to take a photography tour with Keith through the Centro Histórico. Check out the details on his website or shoot him an email: kdannemiller1[at]mac.com. Mention this blog and get a discount!

For more stories about Mexico City’s Centro Histórico, check out: For Whom the Bell Tolls, Candelaria is Coming, La Merced turns 57, the Cult of San Charbel, and a Synagogue Hidden in the Crowd.

Click here to subscribe via RSS

I so enjoyed this interview and the accompanying photos, thanks, Lydia! Might take one of those tours with Keith soon.

Hey Atenea, you should definitely go on one, he has such a great way of opening up the city for people!